ONE DARK NIGHT PRODUCTION

(c)MH

(c)MH

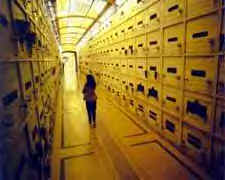

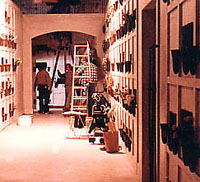

Production was under way in 1982. An interior replica of the Hollywood Mausoleum was built from masonite, plywood and plastic, over a period of three weeks. Another week was devoted to matching the marble look of the walls. Production designer Craig Stearns had worked on creating sets for John Carpenter classics like Halloween, The Fog and Assault on Precinct 13. The art department prepared vans as coroner’s vans, when in reality there are only three coroner’s vans in Los Angeles.

Unlike the relatively unspecific

descriptions of the living dead’s appearance found in scripts by George

Romero, McLoughlin had clear visions of how the corpses should look. "I

didn’t want to use actors for the corpses like all the other Living Dead

movies had before. In the script I described a war veteran, a little girl with a

doll, a bloated guy, a young bride…I was looking for quick emotional

connections to these dead people. An old lady might look like your grandmother

or aunt. We wanted to push those buttons of emotion."

Raymar was clearly

envisioned as a sort of Svengali character. Since Raymar is never seen

alive on screen, instead of using an actor, they went with a dummy built by

makeup expert Tom Burman who was hired based on his impressive effects in the

remade Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Prophecy. With

assistance from Ellis Burman and Bob Williams, while juggling duties for My

Bloody Valentine, Cat People and Halloween III, a

dozen latex rubber corpses were created, including an armless war veteran whose face has

been reconstructed with mortician’s wax to conceal a mortal wound in his skull. Each

of the bodies had endearing nicknames, like Soldier of Misfortune, Elvis Pusley,

Ronald Reagan, Fred and Ethel, Sachmo.

(c)MH

(c)MH

At one point, a very animated arm breaks out from a

crypt and grabs Steve (David Mason Daniels), knocking him unconscious against

the marble. McLoughlin had strived for realism throughout the shoot and

explained was actually Mike Hawes’. "We had no money left for a proper

effect. I wish it had been a skeletal hand instead." To simulate the evil

bioenergy emanating from Raymar’s crypt, a Tesla coil was employed, turning

120 volts of current into 300K volts of lightning.

Bob Summers weaved an atmospheric, foreboding score replete with creeping violins and ominous synthesizers; he also scored The Boogens a year prior. As effective as the score turned out to be, the director had something else in mind. "I had nothing against the score, I was just upset that I wasn’t a part of the process. It’s as if Chuck had to pee on the film to mark his little territory."

The film’s caretaker Martin Nosseck ran an independent projection room in Hollywood. "He created a place where filmmakers could run their dailies. Mike Hawes and I worked as projectionists. He would tell us stories about Howard Hughes. He always wanted to be in a movie. We used to tell him that if we ever made one, we’d put him in it. After we shot his scene, Martin said ‘God bless you. I always wanted to be in a movie and now I finally got to. The next morning, he died. We had no idea he was so sick. By the time they had his funeral, there was his check for his work – it just said Martin Nosseck: Rest in Peace."

As with many movies in

post-production, the ending was changed by the executives. "Our original

ending had the Steadicam moving through an empty crypt, telling the audience

we’re all going to end up here one day" the director explained. The

actual scripted ending was quite different and almost set up a sequel as

McLoughlin explains. "Meg Tilly looks at the camera and we see in her eyes

a hint that Raymar’s powers have passed on to her. It was to bookend the movie

better."

With no backing from ComWorld for their butchering of the ending, McLoughlin and

Hawes gathered up parts of the Stearns set, Leslie Speights and a few corpses to

reshoot their own ending at their own expense - in McLoughlin's own garage, made up to

look like the set.